Introduction

In 2022, many economies around the world began to experience the highest inflation in the last four decades, coupled with recessionary risk and rising public debt. These added new problems to the pandemic, which has been going on for quite some time. In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic swept the world, bringing a huge impact on the economy and society of various countries, such as global production stagnation and economic downturn. Earlier, in 2008, it was the international financial crisis that shocked the world.

Usually, during or after the crisis, the central bank will actively act to hedge risks and control inflation by monetary policy operations, trying to alleviate the negative effects of the crisis. For example, in 2022, the Federal Reserve System (Fed, the central bank of the U.S.) raised interest rates sharply in a row. On March 3rd and 15th of 2020, the Fed urgently cut interest rates by 50 basis points and 100 basis points, respectively. On March 19th 2020, the European Central Bank (ECB) announced the implementation of an emergency asset purchase program of 750 billion euros. Of course, similar large-scale bailouts also occurred during the 2008 international financial crisis.

So how does China’s central bank respond during and after these crises? How effective is its policy implementation? How to understand the new characteristics of China’s economic and financial environment, to optimize the operation of monetary policies? These issues deserve our in-depth study and discussion.

Literature Review

During the 2008 international financial crisis, most central banks first chose to adjust their benchmark interest rates. From September 2007 to the end of December 2008, the Fed cut interest rates nine times, lowering the federal funds rate by a total of 500 basis points. The Bank of England (BOE) and the Bank of Japan (BOJ) have also cut interest rates several times, reducing them to near zero. However, a zero-interest rate policy may introduce a “liquidity trap” and lead to problems such as low consumer confidence (S. Liu, 2010). Therefore, central banks actively explored unconventional monetary policy. For example, after September 2008, the Fed and the ECB frequently introduced new rescue measures, injecting a large amount of funds into the financial system and triggering significant changes in the central bank’s balance sheet. Although these unconventional monetary policies have problems such as imperfect development (Y. Liu et al., 2017) and fail to solve the deep-seated problems that triggered the financial crisis (Zhu & Bian, 2009), central banks are still exploring different monetary policy tools.

In 2020, during the coronavirus pandemic, the Fed., BOJ, and ECB once again exercised many expansionary policies such as balance sheet expansion, making global liquidity extremely abundant to cope with the impact of the epidemic. Gao J. (2020) found that during the epidemic, the PBOC used tools such as the reduction of the required reserve ratio, and re-lending & rediscounting policies, but the total asset scale remained stable. Shan et al. (2023) proved the market-stabilizing function of monetary policy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Guo L. and Wang J. (2020) pointed out that the balance sheets of central banks in other major economies have shown a sharp and rapid expansion trend, but there are significant differences in the balance sheet structure of different central banks. Wei T. (2020) compared the expansion of the balance sheets of Chinese and US central banks from January to May 2020, arguing that the goal of the two central banks is to provide liquidity to the market, but there are significant differences in the speed of expansion and constraints. Funke and Tsang (2020) made a quantitative assessment of PBOC’s response to the coronavirus pandemic and found out the effectiveness of these policies.

In 2022, as the epidemic gradually eased, the global economy began to recover, but new challenges followed, such as the Russian-Ukrainian war. Central banks in the United States, Europe, and other economies were facing new challenges and were actively acting. However, due to time constraints, there are relatively few in-depth studies on central bank operations during the coronavirus pandemic in 2020 and since 2022, and there are few comparative studies linking several crises and the post-crisis era. Although the causes of the international financial crisis in 2008 and the coronavirus pandemic in 2020 are completely different, the macro-financial environment after 2022 is also very different, and the responding measures of different central banks are different, it is valuable to deeply study the changes in the balance sheet of China’s central bank under the two crises to understand the actions of central banks in special periods; Coupled with the observation of changes in the current macro environment and the thinking of optimizing monetary policy, it will help deepen our understanding of the actions of central banks and monetary policy.

The PBOC’s Monetary Policy during the Two Crises

Observing a central bank’s balance sheet is an important perspective in understanding its monetary policy. Therefore, let’s start with a balance sheet observation of the PBOC.

Central banks’ balance sheets consist of assets, liabilities, and owner’s equity. Assets include foreign assets and domestic assets. The former is mainly composed of foreign exchange reserves held by the central bank, and the latter includes credit arrangements provided to financial institutions or other agencies. Liabilities consist mainly of currency in circulation and reserve deposits of the banking industry, i.e. the monetary base, as well as other items such as central bank notes and capital.

From 2007 to 2020, the balance sheet of the PBOC has undergone major changes. In terms of total volume, from the beginning of 2007 to the end of 2020, its total assets rose from 13.25 trillion yuan to 38.76 trillion yuan, an increase of nearly 2 times (see Figure 1). The dotted line above in Figure 1 is the logarithmic value of the total assets, reflecting the magnitude of the change. The curve has been smooth, indicating steady growth. The solid line below shows the monthly growth rate of total assets, which is relatively stable and remains within 5%.

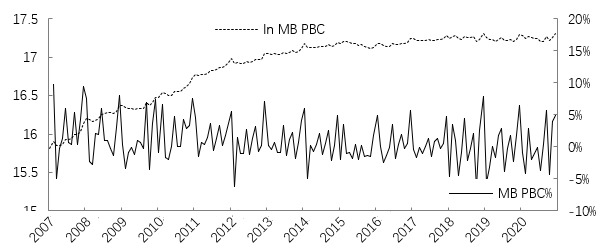

Central bank’s liabilities are mainly composed of monetary base (MB), which changes along with the scale of assets. The dotted line in Figure 2 is the logarithmic value of the PBOC’s monetary base. The curve fluctuates slightly. The solid line below is the month-on-month growth rate of it, which is large and fluctuating significantly.

Specifically, foreign assets have always been the largest asset item of the PBOC. As can be seen from Figure 3, the proportion of foreign assets has been rising from 67.51% at the beginning of 2007 to 84% around 2012. But it dropped significantly around 2016 and has been fluctuating around 60% ever since.

Re-lending and rediscounting of domestic assets (claims on other depository companies) are formed through the central bank’s provision of liquidity to commercial banks. As shown in Figure 3, before September 2014, the proportion of these items to total assets was small and unchanged (basically fluctuating between 3% and 6%), but then began to grow rapidly. Especially in January 2016, this proportion jumped to 15.43%, followed by a lower growth rate; In December 2020, this proportion was already greater than 30%, and there is still an upward trend. The proportion of government claims formed through open market operations has remained below 10%, rising significantly twice in August 2007 and December 2007, from 1.86% to 5.7% and from 5.34% to 9.65% respectively. This proportion slowly declined after December 2007, accounting for about 4% at the end of 2020, and then its absolute amount has remained unchanged for more than two years.

On the liability side, in addition to the MB which is already observed above, the issuance of bonds has also changed significantly. From 2007 to 2020, the proportion of MB in total liabilities was the largest and continued to rise, while the proportion of bonds issued has been declining. As can be seen from Figure 4, the proportion of base currency in total liabilities has increased year by year from 55.38% in January 2007 to remained around 85% from 2013 to 2020. The proportion of bonds issued as a percentage of total liabilities in January 2007 was 25.91%, which began to decline in September 2007, and as of the 2020 observation period, this proportion was only 0.27%, which is almost negligible.

If we compare the PBOC’s policies from the perspective of the balance sheet during the two crises we can summarize the differences in Table 1.

The differences in PBOC’s response to the two crises are mainly reflected in the following aspects:

Firstly, the total volume of open market operations jumped significantly before and after the 2008 international financial crisis, but remained stable during the epidemic, because the purpose and method of these operations in the two crises were different. In 2007, The PBOC indirectly purchased 155 million yuan of 10-year “special Treasury bonds” issued by the Ministry of Finance from financial institutions such as the Agricultural Bank of China to establish the China Investment Corporation Limited, increasing “claims on the government.” Since then, the PBOC has mainly used repurchase agreements to regulate liquidity, which is not reflected in the balance sheet due to the short operation time.

Secondly, the total amount and proportion of re-lending and rediscounting increased, mainly due to its innovation of structural monetary policy tools and transformation of liquidity delivery methods since 2013, which increased the volatility of this subject during the coronavirus pandemic in 2020.

Thirdly, foreign assets have also undergone major changes. After China acceded to WTO in 2001, both the current account and financial account showed a surplus, and the stock of foreign exchange reserves continued to rise. Although its growth rate declined during the 2008 international financial crisis, the total volume of foreign exchange reserves still maintained increasing. In recent years, the growth rate has declined, and so did the proportion of it.

Fourthly, corresponding to the increase in foreign exchange reserves, the PBOC has sterilized partly through the issuance of central bank bills. The proportion of bonds issued to total debt remained above 5% before 2013, and even as high as 25% before and after the 2008 international financial crisis. However, with the slowdown in the growth of foreign assets, the scale of central bank notes has declined significantly, and a small number of central bank notes are no longer used to hedge foreign exchange accounts but play a role in optimizing the yield curve of government bonds and supporting commercial banks to issue subordinated bonds to supplement capital.

In general, the PBOC’s balance sheet expanded during the 2008 international financial crisis, but there was no significant expansion during the 2020 pandemic, as summarized below (Table 2).

In contrast, changes in the PBOC’s balance sheet during the 2008 international financial crisis were more “passive”, mainly through the issuance of notes and other operations to hedge excessive liquidity (Ren, 2009). The monetary policy report for the third quarter of 2020 also confirmed this view and pointed out that this expansion began at the beginning of this century. In addition, due to the limited development of China’s financial market, the lack of ability to actively manage the balance sheet at that time, and the relatively strict capital control, the impact of the world financial crisis on the domestic economy was mild so that the PBOC’s balance sheet could maintain the previous’ level (Wang, 2009).

In 2020, the PBOC’s selection of monetary policy tools and monetary policy ideas are mainly manifested as follows: First, it mainly uses the reduction of required reserve ratio (RRR) and re-lending tools to hedge the impact of the coronavirus pandemic. In terms of RRR’s reduction, in the first quarter of 2020, the PBOC released 1.75 trillion yuan of long-term funds by reducing it; for the use of re-lending and rediscounting tools, three batches of re-lending and rediscounting for different economic entities of 300 billion yuan, 500 billion yuan, and 1 trillion yuan respectively played a positive role in supporting the economy from epidemic prevention and control. Although the RRR reduction may only bring about the structural adjustment of the PBOC’s assets, in the context of the outbreak, the long-term funds released are mainly used to issue loans in the field of inclusive finance, which will cause the tightening of the balance sheet. The re-lending and rediscounting policy will lead to the expansion of the PBOC’s balance sheet, thus ultimately causing the PBOC’s total assets to decline in the first quarter of 2020 while maintaining reasonable liquidity. The PBOC also pointed out in its monetary policy report for the third quarter of 2020 that the balance sheet reduction brought about by the RRR cut and the expansion of the balance sheet brought about by the increase in re-lending offset each other on the balance sheet, keeping the total scale stable.

Secondly, the PBOC is implementing a prudent monetary policy, and proposing to “give full play to the precise drip irrigation role of re-lending and rediscounting to support the development of the real economy”. The PBOC’s innovative structural monetary policy tools have changed liquidity delivery from passive to active, improving the accuracy of liquidity delivery, so re-lending and rediscounting have fluctuated greatly.

It can be seen that due to the large differences in the macroeconomic environment it faces, the PBOC’s actions during the two crises are more obvious, which is mainly reflected in the changes in subjects and overall scale. During the 2008 international financial crisis, the PBOC mainly responded passively, and the balance sheet continued the previous trend. During the 2020 pandemic, the PBOC adopted a more proactive and prudent monetary policy to stabilize its balance sheet and economic development mainly on the domestic economic situation. In addition, since 2013, the PBOC has innovated structural monetary policy tools and changed the way of delivering liquidity, so that the total assets and specific accounts of the PBOC’s balance sheet have changed differently in the two crises.

Analysis of the Policy Effects

The central bank’s balance sheet is a window for its behavior. The changes reflect differences in the macroeconomic environment and monetary policy operations, which ultimately have an impact on the real economy and financial markets. Traditional monetary policy theory generally establishes a model of the mechanism for the operation of the real economy and tests the effects. However, in recent years, with the deepening of the study of the balance sheet of central banks, some scholars tried to directly establish and test the relationship between the size of the balance sheet and the actual economic indicators. Based on the above research, this paper conducts an empirical analysis of the policy effects of PBOC’s total assets during the 2008 international financial crisis and the 2020 pandemic, to increase the understanding of the policy effects of central bank behavior.

The impact of the central bank’s balance sheet could be reflected in prices, income, expenditure, employment, and other aspects (Ireland, 2019). According to the actual situation, the model variables selected in this paper include the month-on-month consumer price index (CPI), the gross domestic product (GDP), and the Shanghai Composite Index (financial market). The macroeconomic data come from the official website of the National Bureau of Statistics of China, and the financial data come from the Wind database. GDP is a total of 56 quarterly data from January 2007 to December 2020, and the rest is a total of 168 monthly data for the same period.

As to the analysis method, we adopt the time-varying parameter vector autoregressive model (TVP-VAR model), which has no assumption of homo-variance and is more realistic than the vector autoregressive model. Its most significant feature is that it allows the variance-covariance and coefficients to adjust over time to capture nonlinear structural changes (Sun & Zhang, 2016). The TVP-VAR model is defined as follows:

\[y_{t} = X_{t}\beta_{t} + A_{t}^{- 1}{\sum_{t} \varepsilon}_{t} \qquad t=s+1,\ldots,n\tag{1}\]

Among them, there are the total assets of the PBOC, month-on-month CPI, GDP, and Shanghai Composite Index; The explanatory variable uses the first-order lag term of itself, which is the correlation coefficient. And time-varying parameters used in the TVP-VAR model are perturbation terms. For specific model settings, please refer to Nakajima J. (2011) and the research group of the People’s Bank of China Guangzhou Branch (2016).

To be fit for the study, it is also necessary to process the data: refer to the data processing methods of Lu W. and Liu C. (2012) and Zou X. (2021), we convert the quarterly GDP data into monthly data with EViews software, and unify the frequency with other variables; Then we take a first-order logarithmic difference for the total assets of the central bank, and a first-order difference for CPI, GDP and the Shanghai Composite Index. The above-processed variables all pass the root of the unity test, and their descriptive statistics are shown in Table 3.

Next, we establish the TVP-VAR model by using OxMetrics6 software. First, we used the VAR model of EViews to determine the order of two lagged period, based on the five indicators such as AIC and SC. Second, we used the variable data of r-lnSIZE, rCPI, rGDP, and rSZ for the TVP-VAR model. Third, the MCMC (Montakaro Method and Markov Chain) algorithm was used to sample 10,000 times. The parameter estimation results of the model are shown in Table 4. The means, standard deviations, confidence intervals and Geweke values obtained by the parameter test results prove that the test conforms to the posterior distribution, and the invalid factors are much less than 10000, which meets the assumption of modeling.

Next, both the equal interval pulse and different time point pulse response analysis are available in the TVP-VAR model. The former is to observe the amplitude of the dependent variable in the equal interval period (periods 2, 4, and 6 are selected to indicate very short-term, short-term, and medium-term periods, respectively) after giving the independent variable a positive impact, while the latter can dynamically observe the changes of the dependent variable at several specified time points.

Firstly, the equispaced impulse response of PBOC’s total assets to several variables is shown in Figure 5. As it shows, total assets have a time-varying impact on various economic variables with different lags: the impulse response to CPI growth in lag 2 is positive in most periods, while lag 4 and 6 have close to no effect. It has no impact on the growth rate of the Shanghai Composite Index lagging 2, 4, and 6; It has a positive impact on GDP growth in lag 2 for most periods, relatively negative in lag 4, and close to no effect on lag 6. In general, the impact of PBOC’s total assets on the economic variables studied in this paper has a significant impact in the short term, and there are stronger fluctuations in the market in more abnormal periods such as 2015, 2018, and 2019. And the impact on financial markets is not very obvious.

Secondly, because the central bank responded most strongly to the crisis in September 2008 and March 2020, this paper selects these two times as the representative points of the 2008 international financial crisis and the 2020 coronavirus epidemic to analyze the time-point impulse response of the central bank’s expansion. From Figure 6, it can be seen that the PBOC’s total asset changes have different impulse responses to China’s CPI growth rate at two-time points: the pulse function of CPI growth rate during the 2008 international financial crisis gradually weakened from a positive value in the current period, and then gradually decreased and converged; However, during the 2020 coronavirus epidemic, it turned from negative to positive in the first phase and converged. The impact of total asset changes on the growth rate of the Shanghai Composite Index differed in the two crises, but eventually converged; The impulse response to the GDP growth rate is quite different: the impulse function during the 2008 international financial crisis gradually turned positive from negative value and gradually converges in the current period; In 2020, the pulse function during epidemic turned from positive to negative, and then turned positive and then converge.

Comparing the time-point impulse response results in the two crises, it can be found that the current impact of the change of total assets of the PBOC on various economic variables in China is significantly different from the international financial crisis in 2008 and the coronavirus epidemic in 2020, which is consistent with the previous analysis found that there are great differences in the PBOC’s actions in the two crises.

Optimal Choices for Post-crisis Monetary Policy

Central banks were active during the crisis, influencing specific economic variables. However, as the epidemic gradually enters into a new period of normalization, the macroeconomy has begun to take on new characteristics, which require close attention from the PBOC. Since 2022, many countries around the world have faced high debt and economic “stagflation”, and fiscal dominance is more popular (IMF, 2021). China’s fiscal revenue and expenditure, especially local fiscal revenue and expenditure pressure, is also relatively large, and fiscal-led scenarios are frequent. The importance of improving the overall efficiency of the use of public sector funds has become increasingly prominent. In this context, the central bank needs to guide the change of social concepts, take the establishment of a modern central banking system as an opportunity, consciously and actively withdraw from some quasi-fiscal functions, and accelerate the establishment of a monetary policy framework suitable for China’s economic and financial conditions, to improve the effect of monetary policy.

Firstly, we should clarify relevant cognition and guide the change of social concepts. At present, “the Ministry of Finance (MOF) cannot directly overdraft at the central bank” has become the mainstream of cognition, but there are still some misunderstandings in terms of the relationship between MOF and the central bank. So, we need a clear boundary between Finance and the central bank under the consideration of overall interests. Indeed, the MOF and the Central Bank are most efficient when their functions are clear and perform their respective functions. The central bank is responsible for implementing monetary and exchange rate policies, maintaining financial stability, etc., and if losses occur in the performance of duties, the MOF will make up for them; Profits generated in the course of operation shall also be handed over to the MOF by the law. The central bank independently operates in the open market and does not implement special monetary policies for specific groups, industries, and sectors, to prevent the transmission of interests.

Secondly, both MOF and the central bank should perform their respective duties, which can effectively avoid the moral hazard or misuse of the central bank, improve the ability of the central bank to stabilize prices, and maintain macro-financial stability as a lender of last resort; Moreover, the budget constraint of fiscal funds should be strengthened, the use of funds that are not subject to social supervision such as people’s congresses in broad government funds should be avoided, and then the overall efficiency of the use of public funds can be improved. The PBOC should intentionally guide all sectors of society to correctly understand and evaluate the coordination and cooperation between fiscal policy and monetary policy, and try to prevent the Ministry of Finance from overdrawing or borrowing from the central bank in a disguised way of evasion or adding the central bank to assume quasi-fiscal functions. It is not appropriate to pass on some fiscal expenditures to commercial financial institutions in the name of the real economy of financial services.

Thirdly, improve the independence of the central bank. According to the experiences of many central banks, the improvement of central bank independence can significantly reduce inflation. This is also reflected in the practice of the central bank after China’s reform and opening-up.

After the promulgation of the PBOC Law in 1995, the number of direct overdrafts from the MOF to the central bank was significantly reduced, but the phenomenon of indirect overdraft and transfer of fiscal expenditure responsibilities came into being. First, the number of policies relending is huge, with the nature of fiscal overdraft, and the losses that should be borne by the Finance are finally undertaken in the central bank’s balance sheet. Second, the loan losses in the process of economic transformation that the finance is unwilling to or unable to bear are digested by the central bank, such as state-owned commercial banks, rural credit cooperatives, and other financial institutions. Third, the pass-through of fiscal expenditure has always existed. If there are problems in state-owned enterprises and large private enterprises, commercial banks are required to help them; Problems in financial institutions and financial markets should be solved by the central bank. For example, the recent problems of real estate development enterprises mainly rely on commercial banks and central banks to alleviate them.

At present, affected by the impact of the epidemic, the downturn in real estate, and tax and fee reductions, the recent fiscal revenue and expenditure, the fiscal revenue and expenditure of local governments are relatively tight. In the medium and long term, on the one hand, under the situation of slowing down the growth of disposable income and continuous insufficient consumption, the pressure to adjust the income share of government departments and residential sectors in national income will increase; On the other hand, in the future, China’s space for relying on high economic growth to alleviate the contradiction between fiscal revenue and expenditure is getting smaller and smaller. Under the circumstance that the contradiction between fiscal revenue and expenditure increases, the pressure to require commercial banks and central banks to bear part of fiscal expenditure in various ways will increase. For example, transferring foreign exchange reserves to government agencies, requiring commercial banks to yield profits, and handing over profits by the central bank. According to the classification of the IMF (2021), transferring foreign exchange reserves to government agencies and handing over profits by the central bank are typical fiscal-led behaviors and so on. In such an environment, the central bank should consciously take the initiative to reduce the quasi-fiscal behavior it bears and continuously enhance its independence.

Summary

This paper first reviews and compares the actions and effects of the PBOC under the international financial crisis in 2008 and the global covid-19 pandemic in 2020, based on the perspective of its balance sheet. First, the changes in the total assets of the PBOC continue the trend before the crisis, expanding during the international financial crisis in 2008 and fluctuating in 2020 without significant expansion. Second, there are obvious differences in the actions of the PBOC’s balance sheet during the two crises, due to macroeconomic and monetary policy stances. Third, the impact of the PBOC’s expansion on China’s economic variables is obvious in the short term, and the impact on the financial market is not large.

This paper also focuses on the main challenges faced by China’s central bank and the optimization of monetary policy choices due to the great changes in the domestic and foreign financial environment since 2022.

The impact of the pandemic on the economies of various countries continues, and central banks are still actively responding through monetary policy means. Based on the above research, this paper makes the following recommendations:

Firstly, focus on the size of the central bank’s balance sheet. Changes in the total size of the central bank’s balance sheet and important accounts can reflect the general trend of China’s monetary policy to a certain extent; According to the point-in-time impulse response chart, the impact of the central bank balance sheet scale and money supply on the real economy and financial system during the crisis is similar, but in reality, the data statistics of the former are more timely and accurate than the latter, so they can be used as an effective supplement to observe monetary policy.

Secondly, actively use monetary policy tools in a crisis to keep markets reasonably liquid, and direct relief measures can be used. Innovative monetary policy tools have enabled balance sheet changes while maintaining the stability of the base currency, which in turn has a more positive impact on the real economy and the financial system; However, the impulse response results show that monetary policy has a certain time lag and limited effect, and some direct rescue measures may be more rapid and effective.

Thirdly, improve the independence of central banks, but be wary of the negative effects of innovative monetary policy operations such as structural monetary policy when making full use of them. Structural monetary policy is relatively less constrained by laws and financial markets, and may largely subsidize a small number of financial institutions, specific industries, and groups, with obvious distributional effects. Moreover, this is partly because the central bank’s public fund spending (rather than fiscal money expenditure) is largely unconstrained by the fiscal budget system.